Results

Local Challenges

Drechtsteden region (NL)

Marche region (Italy)

Grand Reims (France)

Mahiliou region (Belarus)

Value of public participation

The awareness and formal acknowledgement of including different stakeholder interests into the decision-making processes about urban development has increased significantly. Landscape transformations combine top-down regulation and bottom-up governance initiatives. The top-down regulation is based on an aesthetic heritage, and had developed a local based approach to reconcile protection and development. Elected people consider themselves as legitimate to decide for their community. Participatory processes vary a lot according to the scale of project and processes, and first challenge is free access to information regarding territorial transformations. Governance of urban landscape quality is complicated by the fact that participants do not constitute a homogeneous group…

The awareness and formal acknowledgement of including different stakeholder interests into the decision-making processes about urban development has increased significantly. Landscape transformations combine top-down regulation and bottom-up governance initiatives. The top-down regulation is based on an aesthetic heritage, and had developed a local based approach to reconcile protection and development. Elected people consider themselves as legitimate to decide for their community. Participatory processes vary a lot according to the scale of project and processes, and first challenge is free access to information regarding territorial transformations. Governance of urban landscape quality is complicated by the fact that participants do not constitute a homogeneous group.

Rural landscape development shows examples of public responsibilities carried out together with or exclusively by citizens. The actual participation of certain groups remains a challenge (often repeatedly the same actors do participate: well-educated and strong socioeconomic milieus tend to engage intensively). Moreover, when you involve people early in the process, they are more motivated because they see the still possible influence in the opinion framing and decision-making. However, there is a sort of untrust in Institutions that makes very difficult for some stakeholders to be interested because they don’t see their voices heard and they don’t trust the process itself.

Local knowledge and community participation are still not seriously taken into account, and sometimes the participatory procedure is used as mere justification of governance choices. There is still a sign of significant decentralization of power. On global landscape issues, there is a real collaboration between local and national institutions, but a gap persists between national objectives and local issues. In Italy, Tuscany region has adopted a regional law that defines who may participate, and that guarantees the participation and the methodology to be followed. The real risk is that this is transformed into procedural compliance that must necessarily be carried out.

In France, photographic observatories involve institutional and local actors. Landscape management tools have been developed such as “Regional Landscapes Atlas”, and “Landscapes Plans” at a local and inter-municipalities level. They make work together the main stakeholders: researchers, civil servants, economic operators, associations, etc. Landscape Plans require specific governance —hold by a steering and a technical committee— to decide with inhabitants, which landscapes have to be protected or have to evolve, and how to make them evolve.

Increasing this kind of dialogue with citizens is a way to modify behaviors or to enhance awareness about biodiversity and climate change. On their side, landscape designers develop mediation processes with inhabitants, through collective restitution. Even economic operators or developers try to create partnerships and common interests. So, landscape is a medium to express implicit conflicts; it helps to connect actors, scales and objects. Urban agriculture shows that understanding and planning practices change over time. This change involves learning processes, in which co-creation experiences function as proactive tools for better access and distribution of environmental benefits.

Implementing the European Landscape Convention

The aforementioned landscape challenges are pressing issues prevailing in different geographical contexts all over Europe, but each landscape context brings about specific regional challenges depending on the particular socio-spatial environment. Tackling these and finding ways to deal with conflicting interests of land use in European landscapes were the reasons for deliberating and defining the European Landscape Convention (ELC). The convention has since then been ratified by 39 European countries (but not by Russia)…

The aforementioned landscape challenges are pressing issues prevailing in different geographical contexts all over Europe, but each landscape context brings about specific regional challenges depending on the particular socio-spatial environment. Tackling these and finding ways to deal with conflicting interests of land use in European landscapes were the reasons for deliberating and defining the European Landscape Convention (ELC). The convention has since then been ratified by 39 European countries (but not by Russia).

In fact, several of the stakeholders interviewed had not even heard of the ELC. Only the spirit of the ELC is familiar. However, the ELC is partly taken up as one of the guiding principles in the state Acts. By implementing this, the government wants to combine and simplify the regulations for spatial projects and environmental laws. The actual legislation is too complex for diverse actors. For example, it further emphasizes a separation between “landscape protection” and “landscape enhancement”.

The citizens will play a more prominent role in the future of landscape decision making. The principle of decentralizing environmental and planning decision-making leads to a shift in responsibilities from the national level to the level of provinces and municipalities. But consultation processes are not fluid and some municipalities believe that the EU’s recommendations are not applicable at their level, due to a lack of financial, technical or human resources. Each year, a European Workshop for the implementation of the ELC allows to share ideas, practices, experiences and achievements.

From the perspective of landscape researchers and landscape NGO’s, the ELC is seen as a valuable description of how landscapes shall be understood and governed. However, a main review addresses its broadness and non-binding status, without setting rules for punishments. The ELC is, in fact, a soft law based on ‘voluntary’ membership of States; it is mostly perceived as a cultural reference. In that sense, the ELC can even be counterproductive with respect to reach targets of protecting and acknowledging the values and (ecosystem) services of (green) landscapes.

Decision Making tools

These decision-making tools are intended for elected officials and planners in order to improve the quality of landscapes and the quality of life of inhabitants.

Work plans

WP 1 Methodology

The approach foreseen for WP1 focuses on an academic literature and document analysis, complemented with a series of several expert interviews. In order to identify the key stakeholders related to landscape development in urban contexts, we have conducted a stakeholder analysis in two steps.

The approach foreseen for WP1 focuses on a literature and document analysis, complemented with a series of several expert interviews. In order to identify the key stakeholders related to landscape development in urban contexts, we have conducted a stakeholder analysis in two steps.

First, we consulted the current scientific literature on landscape change and decision-making in landscape governance. Based on the insights, we conducted a series of 49 expert interviews. The team developed a guideline for structured interviews. This guideline contained open and closed questions addressing:

1) the main issues and developments in the governance of urban landscape quality;

2) the decision-making procedures and involvement of agencies and stakeholders;

3) the value of stakeholder and citizen participation in urban landscape governance;

4) the implementation and uptake of the ELC;

5) the identification of new, relevant documents and stakeholders.

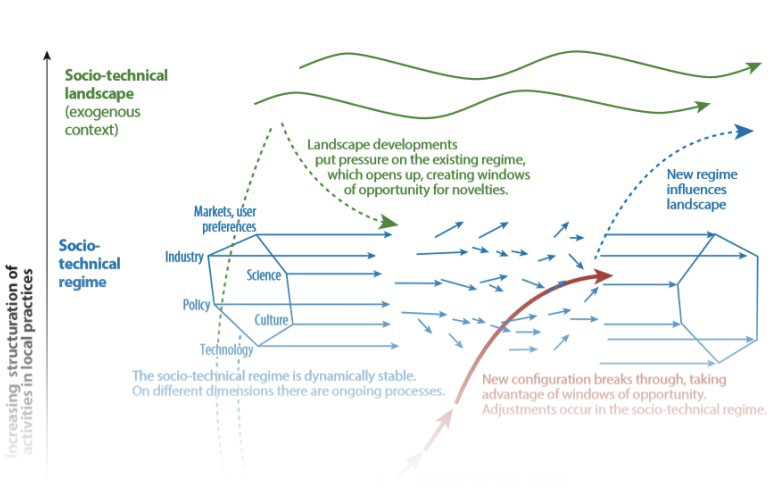

Next to the stakeholder analysis, the project team also realized the need to elaborate on the key concepts and theories being essential in the course of this study, such as landscape quality, landscape policies, integrated approach for urban landscapes, sustainability transition perspective, transition governance, participatory involvement or integrated landscape governance (adaptive planning, urban living labs and joint fact-finding).

Resources:

WP 3 Methodology

The approach foreseen for WP3 has been divided into 2 parts. The first part concerned the analysis of urban regions, based on the results of WP1 and WP2. The aim was to analyze the urban development of each region of study through cartographic data and institutional reports. Major urban transformations and the relationships between rural and urban dimensions are then highlighted.

The approach foreseen for WP3 has been divided into 2 parts. The first part concerned the analysis of urban regions, based on the results of WP1 and WP2. The aim was to analyze the urban development of each region of study through cartographic data and institutional reports. Major urban transformations and the relationships between rural and urban dimensions are then highlighted. The morphological analysis of the urban-rural continuum is carried out through a photographic transect. It is related to the significant legislations and urban strategies of local councilors to understand the gap between the political visions of urban regions and the main local challenges. The second stage concerned an analysis of two case studies per urban area. The selected cases are in a (peri-)urban context, reflect concrete problems in terms of urban greening as part of the transition to sustainability, are relatively informed (availability of data to analyze the decision-making process), involve a diversity of actors in the decision-making process and require a variety of knowledge. For each case study, the process of setting the political agenda is described and mapped to highlight the early problems, how local authorities collect information on the quality of the urban landscape and how this information is used (or not), including local knowledge through participatory procedures. This understanding was achieved by articulating data from case study documentation and interviews with stakeholders (local authorities, planners, associations, etc.). The transformations of these case studies were then evaluated by indicators selected in the QLand / QLife tool in relation to the WP2 results. Aim was to understand the conditions of the transition to sustainability in a situation.

Resources:

WP 2 Methodology

WP2 addresses the questions: How do stakeholders evaluate the urban landscape quality of their respective regions, especially the dynamics of green, red, grey and blue? Which different perspectives can be articulated on transformations in the urban rural continuum and what can be learnt from comparing the regional perspectives?

WP2 addresses the questions: How do stakeholders evaluate the urban landscape quality of their respective regions, especially the dynamics of green, red, grey and blue? Which different perspectives can be articulated on transformations in the urban rural continuum and what can be learnt from comparing the regional perspectives?

The project uses the repertory grid technique in combination with statistical analysis for identifying the range of perspectives. Repertory grid is a bottom-up interview technique, which avoids steering the interviewee by questioning (Kelly 1955; Fransella et al. 2004; Dunn 2001). The goal is to articulate the underlying dimensions through which stakeholders evaluate their immediate environment. Interviews concentrate on comparing triads of ´elements´. Smart-U-Green use pictures of typical urban landscape elements (Vasileiadou and al. 2013). The returning interview question is: which two elements are similar and how are these different from the third? In answering this question interviewees articulate bipolar constructs, such as man made – natural, healthy – unhealthy, good memories – bad memories, etc. When the interviewee has articulated about 10-20 constructs, (s)he will select the three that (s)he considers most relevant for evaluating the desirability of urban landscape transformations. The result of statistical analysis is a point cloud, which visualizes the distance between the elements as perceived by the interviewees. Clusters of elements constitute a perspective, which needs interpretation using the qualitative interview data.

The results were entered in SPSS Statistics Version 25. The results of the evaluations of the set of pictures were defined as variables in the SPSS data sets. Therefore, variable 1 is the evaluation of the 18 pictures by participant 1 on his/her first construct, and so forth. One interview was excluded due to missing data in the results, the remaining interviews did not include missing values. As such, there is no universal scale that respondents used to evaluate the elements. The dimension of the data was reduced via Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA). MCA, or homogeneity analysis divides the 18 pictures into homogeneous subgroups. The subjective evaluations of the interviewees are considered homogeneous when pictures are classified in the same subgroups (IBM SPSS Categories 25). The evaluation of two constructs per participant were defined as analysis variables, while the pictures were defined as labeling variables. A joint category plot was created resulting in a two-dimensional plot from picture 1 to 18. Pictures which are similarly evaluated by the participants are indicated with dots lying close to each other, dots lying apart indicate a contrast in evaluation (Van de Kerkhof et al. 2009). An MCA was conducted for each region and one additional MCA was conducted including results of all regions.

Resources: Set of pictures used for WP2

Smart Urban Green Reports

Work Package 1 Report

Governing conflicting perspectives on transformations in the urban-rural continuum

February 2019